While the development of COVID-19 vaccines is considered “the fastest in history,”[1] the same could not be said for its deployment. Currently, the global vaccination drive is being hindered by neoliberal policies with predominant focus on enabling capital to gain more profit.

Vaccine access today is but one element in the larger conversations involving working people’s rights to free and accessible healthcare, social services, and other social and economic rights that urgently need to be addressed by shifting away from the dominant economic system.

Monopolisation through patents

Pharmaceutical research has become less about finding breakthroughs in drug development and more about restricting access and protecting their sources of super-profits.

Patents grant exclusive rights to produce an invention, and for a certain time prevents other businesses from copying and selling it without the license of the patent-holder.[2] Laws and administrative measures to protect intellectual property rights had its roots in Europe, particularly in Venice, during the Renaissance period.[3] At the time, advancements in technology and in other fields have attracted artisans and inventors from elsewhere seeking legal protection from infringers.

Because patents provided some degree of economic privilege, it has always been susceptible to abuse. European royal courts, especially in Great Britain, used to grant patents on even household commodities to favored courtiers. That is, up until the declaration of Statute of Monopolies, in which only novel inventions can be granted patents.[4]

Throughout history, the patent system had evolved through variety of amendments in some countries especially during and after the first Industrial Revolution, where technological advancements have enabled innovations in different fields, including in medicine. The matter of whether medicines should be patented or not had been hotly debated in Europe. But even then, many pharmacists and medicinal researchers have opposed patenting of medicines as it would “threaten the open circulation of knowledge, and hinder public access to therapies essential to life.”[5]

Meanwhile, in the United States (US), pharmaceutical companies have long enjoyed privileges such as patent protections and market exclusivity for medicines and drugs. These have culminated in the 1984 Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act[6] in the US, which maintains that these privileges compensate for the high risk and cost of developing new medicines. But once the patent expires, transnational corporations (TNCs) should relinquish intellectual property rights to “encourag[e] competition and innovation.”

In reality, pharmaceutical corporations under this system have had free rein to utilise tactics such as expansive use of “patent thickets”—overlapping patents among companies which entangle competitors in a web of licensing negotiations and infringement cases.[7] The top 12 brand drugs on the US market in the previous year, which include treatments for arthritis, cancer, and diabetes, are covered in these “patent thickets” consisting 848 patents (71 per drug), averaging 38 years without generic competition, according to a recent report.[8]

Pharmaceutical TNCs also employ a tactic called “product hopping,” as in the case of British-Swedish corporation AstraZeneca, for instance. This means making minor changes in a drug to re-brand its expiring patent in an effort to block new competitors.[9] Pharmaceutical research has become less about finding breakthroughs in drug development and more about restricting access and protecting their sources of super-profits.

A worldwide headache: Neoliberal trade

Corporations’ pursuit of profit has reached levels so extreme, that they would rather not grant access to people in need of treatments to block competitors and secure more revenue.

At the international level, many countries from the global South have been struggling for decades against TNCs raking in super-profits from patented products by virtue of intellectual property rights[10] as pharmaceutical TNCs funnel profits in addition to what they could have had without monopolistic control. Pharmaceutical TNCs also take advantage of Southern countries’ inadequate and underfunded drug regulatory systems, including their bureaucratic processes, in order to keep generic drug manufacturers away from the local market.[11]

Since the establishment of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995, its Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement has been safeguarding patents and copyrights internationally, extending to vital end products such as new diagnostics, vaccines, medicines, and medical supplies.[12] While amendments to TRIPS supposedly conceded possibilities of exporting low-cost medicines to developing countries amid public health problems such as tuberculosis and HIV-AIDS,[13] the TRIPS itself remains in force, and pharmaceutical TNCs and its lobbyists[14] never stopped pressing for more severe intellectual property protections around the world.

Corporations’ pursuit of profit has reached levels so extreme, that they would rather not grant access to people in need of treatments to block competitors and secure more revenue. Sample cases include Pfizer’s price hike on pneumonia vaccines (with prices in 2015 increasing 68 times compared to 2001)[15] and Johnson & Johnson’s refusal to grant access to three of its HIV drugs for which it holds key patents.[16] Corporate capture, facilitated by neoliberal policy, unravels the system of intellectual property rights that has been driving dependence on medicine imports. At the same time, it deprives many countries in the global South of the opportunities to advance their own research and development, and from using technologies and important knowledge for their economic and social objectives. It has become a matter of life-and-death today.

Profiteering from the global pandemic

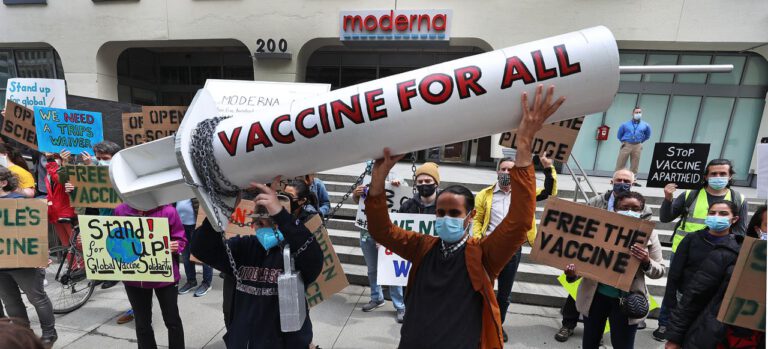

Amid the first year of the global pandemic, US-based TNCs Pfizer, Moderna, and Johnson & Johnson experienced a surge in revenue, raking in a total of USD125.3 billion. Their profiteering as the pandemic raged has since left the global vaccination effort at the hands of the market, in utter disregard of the consequences. The present vaccine production is nowhere close to delivering the projected 10 to 15 billion doses needed. And at the current rate of the global vaccine roll-out, countries in the global South are unlikely to vaccinate most of their population before 2023 or 2024. By that time, newly developed variants may risk rendering existing vaccines ineffective.

Amid the first year of the global pandemic, US-based TNCs Pfizer, Moderna, and Johnson & Johnson experienced a surge in revenue, raking in a total of USD125.3 billion,[17] with Moderna’s total income growing 13 times from 2019.[18] Pfizer earned USD4.9 billion for the first three months of 2021 and is forecasting revenues from its vaccines to reach USD26 billion for the year.[19]

Their profiteering as the pandemic raged has since left the global vaccination effort at the hands of the market, in utter disregard of the consequences. The present vaccine production is nowhere close to delivering the projected 10 to 15 billion doses needed.[20] At the end of April this year, only 1.2 billion doses had been produced worldwide.[21] And at the current rate of the global vaccine roll-out, countries in the global South are unlikely to vaccinate most of their population before 2023 or 2024.[22] By that time, newly developed variants may risk rendering existing vaccines ineffective. The world economy would have remained crisis-ridden in the face of possible losses of more than USD9 trillion[23] due to global supply chain disruptions even with high-income nations fully vaccinated by mid-2021.[24]

Right now, a handful of high-income countries have secured most of all the COVID-19 vaccines. Despite Pfizer and Moderna promising to increase vaccine production, they still continue their for-profit model that prompted the initial vaccine shortage in the first place.[25] Deeply indebted Southern countries which have cut funding for basic services such as public health and education due to the pandemic[26][27] are being mired deeper in debt as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) proposes a USD 50 billion Vaccine Plan, which would be financed through grants but also through existing lending mechanisms of international finance institutions. [28]

Table 1. Major COVID-19 vaccine manufacturers today

| Major manufacturers | Total Doses Contracted

(as of March 2021) |

| AstraZeneca/Oxford | 2.8 billion |

| Novavax | 1.4 billion |

| BioNTech/Pfizer | 1.1billion |

| Gamaleya | 524 million |

| Moderna | 761 million |

| Johnson & Johnson | 344 million |

Source: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1195885/covid-19-vaccines-by-contract-size/

In October last year, India and South Africa requested that the WTO TRIPS Council consider a temporary waiver to suspend intellectual property obligations on all medical products needed to control the COVID-19 pandemic.[29] And while the Biden administration in the US has so far conceded after campaigners’ work, the issue is far from resolved as WTO itself requires consensus. Conversely, the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) — representing some of the largest drug companies in the world — continues to lobby to instead protect intellectual property rights during the pandemic,[30] and warns that China will profit from suspending TRIPS.[31]

Big Pharma’s interest in profits comes at the expense of lives. In the long run, this might lead to the protraction of the pandemic, and along with it, the continued acceleration of the growing inequality around the world. The concentration of capital in the pharmaceutical industry is matched by growing wealth of billionaires. By end-2020, there are 56 new billionaires from the US amid the pandemic.[32] By May 2020, the vaccine monopoly has directly created nine new billionaires, whose combined worth of USD19.3 billion is “enough to fully vaccinate all people in low-income countries 1.3 times.”[33]

On the other hand, the situation of working peoples suffering from job insecurity, unemployment, lower incomes, and hunger, all increase their vulnerability to illness. The right to health is closely linked with people’s economic rights. Inaccessible social services, from power and water, to decent mass housing and transportation systems, prevent them from being able to properly self-quarantine, and perform other basic preventive measures. Countries in the global South, such as India, Myanmar, Brazil, and Colombia, continue to tread the path of repressive rule in the context of the pandemic.

People-centred solutions, not profit

The world could look into both Vietnam’s and Cuba’s healthcare system for possible lessons. Vietnam’s outstanding response to the Coronavirus was based on people’s solidarity in caring for vulnerable groups. Publicly funded institutions in Vietnam have delivered four COVID-19 test kits that are locally made. Cuba’s commitment to people’s universal right to healthcare has enabled it to locally produce the vaccine Soberana 2, which is entering third phase of the trials.

It is high time for the global community to consider a shift. For instance, the world could look into both Vietnam’s and Cuba’s healthcare system for possible lessons.

Vietnam, despite having been among the countries at the forefront of the Coronavirus’ initial spread, has maintained minimal number of cases. Today, the country has recorded a little over 5,000 cases and only 41 deaths.[34] This success has been attributed to Vietnam’s “rigorous public health measures” and a current health system that “enabled the government to decentralise treatment for COVID-19 while maintaining its effectiveness.”[35] Vietnam’s outstanding response to the Coronavirus was also the result of coordination of national and sub-national entities of its government, which emphasised people’s solidarity in caring for vulnerable groups.[36] Publicly funded institutions in Vietnam have worked with the country’s Ministry of Defense and the National Institute of Hygiene and Epidemiology to deliver four COVID-19 test kits that are locally made.[37]

Cuba, for its part, had kept coronavirus infections for most of 2020 in incredibly low levels.[38] Today, its vaccine candidate Soberana 2 is entering third phase of the trials.[39] Its successful response to the global pandemic was largely due to “years of investment and diligent attention to primary care and people’s health.”[40] The country has also a “comprehensive, nationalised health system and one of the highest doctor-to-patient ratios in the world.” Its system focuses gathering research on community needs,[41] and is guided by some fundamental basic principles and policy goals such as people’s universal right to healthcare.[42]

This people-oriented, community-based approach is needed today, more than ever. The pandemic has made it clear that neoliberalism and the monopoly capitalist system—especially the TNCs as supported by key global powers—are incapable of pulling us out of the crises in which they have shaped, and have even found ways to thrive. Fighting TNCs in the pharmaceutical industry demands linking with the broader struggles of people’s organisations and social movements for people-oriented pandemic responses.[43]

In the long-term, shifts away from the policies of privatisation, deregulation, and liberalisation of economies would be necessary. Shifts should include building national industries, and developing local capacity in research and development in science and technology. These trajectories are part of laying foundations for self-sufficient production for basic needs. All are part of asserting genuine development for peoples in the global South. #