March 8 of this year is the first International Working Women’s Day after the Covid-19 pandemic devastated the peoples of the world. How has the pandemic affected working women, especially in the global South?

By now, it is already a truism that the pandemic has highlighted and heightened historical and systemic inequalities, and has brought about a crisis that is worsening other existing crises.

While Covid-19 affects women less than men, working women, especially in and from the Global South, are highly exposed to the Coronavirus. They carry in their shoulders the heaviest socio-economic and emotional-psychological burdens caused by the pandemic.

Mass layoffs, work reduction and wage cuts have affected workers — and working women, who were receiving lower wages and were in less secure jobs, are first among those affected. An early study from the ILO said that 140 million full-time jobs will be lost because of the pandemic, and women’s employment is 19 per cent more at risk than those of men.

Out of all employed women, 40 per cent were working in economic sectors worst hit by the pandemic, compared to only 37 per cent of employed men. Even among OECD countries, reputed to be more advanced in gender equality, 17 out of 24 countries that reported heightened unemployment said that women were affected more adversely.

There is little to no unemployment benefits and social protection in the global South. Women compose the majority of single parents, and being laid off from work means no food to feed children. Many couples, meanwhile, were forced to choose who would give up working and that, frequently, is the wife, the lower earner.

Massive job loss among women has forced commentators to say that the pandemic is a disaster for women’s hard-fought and still-woefully lacking independence. Meanwhile, women who were retained in their jobs grapple with health and safety issues in the workplace, largely dependent on employers’ observance of protocols and government’s enforcement of these.

Among the rural population, who make up three-fourths of the world’s poor, the disruption of the agricultural food chain and activities have brought about greater hunger and poverty, especially for women farmers.

Women who are informal agricultural workers were easily laid off from work, and unemployment benefits are unheard of. Women who farm in small lands have met difficulties in selling their produce. These situations leave women farmers without savings to support their families while waiting for the next harvest season.

Women farmers usually find it difficult to access land, labor and capital — and even credit and social protection. It is still usually the males of the family who are recognized for availing these, and female labor is considered a mere adjunct of male labor. As such, women farmers are finding it difficult to buy seeds, fertilizers and other farm inputs.

In many parts of the world, various hindrances to women’s ownership of lands exist and persist, and the return of unemployed migrants from the cities means greater competition for land. As pressure to work in the farms increases, demand for work at home has also increased. During crises, women farmers usually cut their food intake so that their children can eat, sacrificing their body’s health.

Across the globe, people have been forced to stay in their homes. This means more unpaid work at home — from cleaning the house to taking care of kids and the elderly. These are roles that are traditionally shouldered by women — by wives and mothers, women working in day-care facilities, or domestic workers.

Children’s schooling from home has also meant additional expenses and additional work shouldered by women. Even women in the middle classes who are working from home face increased domestic chores. Working women now have even less time for rest, leisure or creative pursuits.

The economic and other difficulties caused by the pandemic are also forcing families to stop sending their children to school, and again, girls face the greater problem. Estimates show that 11 million girls may leave school by the end of the pandemic and that many among them will not return.

The home has seldom been a safe space for working women and their daughters. In many parts of the world, the pandemic has resulted in an increase in domestic and sexual violence, as triggers of the phenomenon have worsened: stress, alcoholism, financial and other difficulties.With joblessness and poverty on the rise, working women will find it more difficult to leave abusive husbands.

Aside from facing the pandemic’s negative socio-economic effects, working women and women in general have also been struggling with its emotional and psychological effects.

In the battle against the pandemic, health systems are in the frontlines. Around the world, it is highly gendered, as an estimated 70 per cent of the profession’s workforce is composed of women. In advanced capitalist countries, it is also highly racialized, employing a significant number of migrant workers.

The pandemic has made health workers in the highly privatized healthcare systems of the global South more overworked and underpaid, and there is also a huge gender pay gap in the profession.

Women health workers are battling with disease and death, and not only those afflicting their patients but also those threatening them. And healthcare systems in the global South have been rendered weak by decades of neoliberal policies.

There is no debate among observers: overall, the pandemic has meant greater poverty and suffering for the working peoples of the world — and that working women bear a great share.

One study says that the pandemic will bring 96 million people to extreme poverty this year, and 47 million of them are women and girls. That would bring the number of women and girls living on USD 1.90 or less to 435 million worldwide.

Capitalism has always been harsh towards working women and the peoples of the global South. It is even more so during times of crises such as the pandemic.

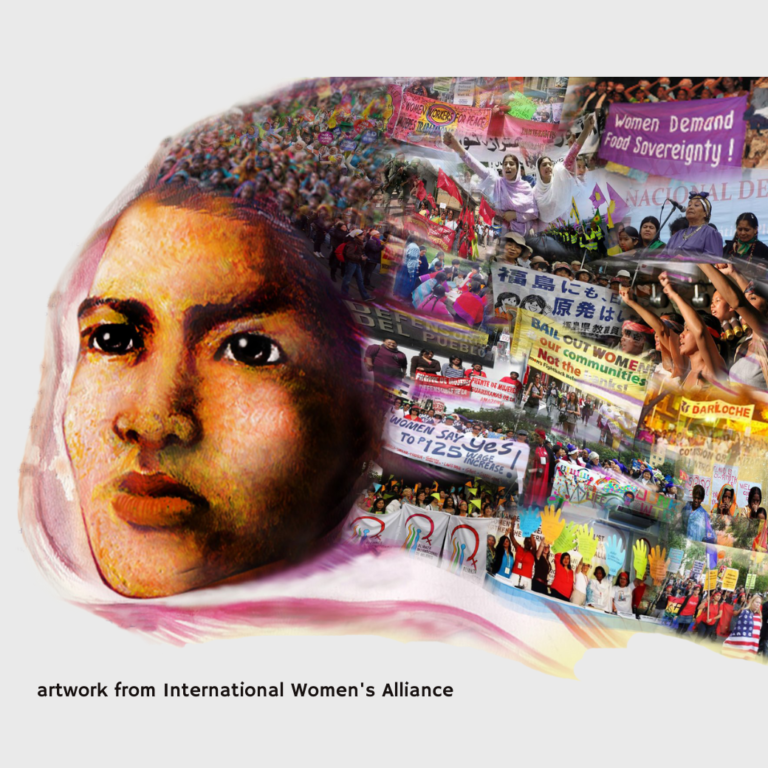

It is therefore not surprising that women have figured prominently in protests that have rocked governments and systems in the past year: from demonstrations against police killings in the US to mobilizations against the military junta in Myanmar, from the movement for a new constitution in Chile to farmers’ protests against farm laws in India and condemnation of police brutality in Nigeria.

Observers around the world have been warning that because of the poverty and suffering that the pandemic is aggravating, it will also trigger social and political unrest. With the burdens caused by the pandemic weighing heavily on their shoulders, the working women of the world will continue leading the protests. They have every reason to do so.###